What was a residential school?

With stories of mass child graves being discovered more and more in recent news, a lot of people have been wondering what actually happened with residential schools in North America. A part of our shared history that’s often forgotten or deliberately covered up, the story of this era is important to investigate and understand.

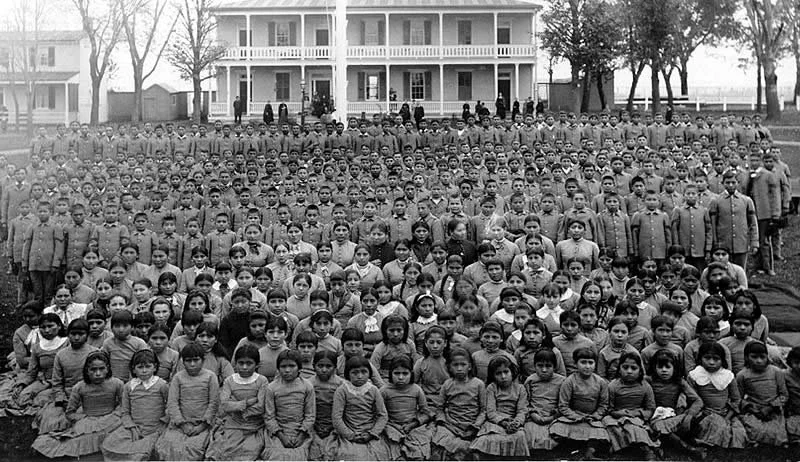

An early image of students at a boarding school, being forced to dress in “American” clothing

Recently, here in my city of Albuquerque, a plaque honoring the children that were buried in a mass grave at one of these schools went missing. The crime, while minor, has continued to shine a spotlight on the history of these schools that has been long forgotten. After more of these types of mass graves were discovered in Canada, federal Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, vowed in June to review the situation in the United States. Haaland said her department would “address the intergenerational impact of Indian boarding schools to shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past, no matter how hard it will be.”

As light continues to be shed on the atrocities that were committed in these schools, it’s important to me that my community here at Native Knitter knows what happened and knows that their questions, curiosity and discussion about these things are welcome. If we can’t learn from the past, we are bound to continue repeating the mistakes of those that came before us. So I’m using this space as a way to open up some dialogue and look to a brighter future for everyone.

The reality of these boarding schools is that they were created to force Native American children to assimilate into Euro-centric “American” culture. State-sponsored officials began to make the rounds among various tribal communities in North America, manipulating or even forcing families to send their children to American or Canadian boarding schools. Many times, children were removed from their families against the wishes of their parents. For some, they believed that allowing their children to go to school would benefit the child or the family, but when the children arrived at the boarding schools, all cultural signifiers and ties to their families were methodically erased. These schools were federally approved by the US government, and mostly run by Christian missionaries, with the stated intent of educating and “helping” these children thrive in a European-American culture.

The conditions at these schools were truly awful, and something that seems almost unbelievable to us today. After being torn from their families, or lied to in order to allow their “release” into official care, these children and their families experienced ultimate heartbreak and disrespect. The kids were given white names (some too young to even remember what their family name was), forced to speak English and were not allowed to practice their culture. Their hair was cut and their religions were forbidden. They took classes on how to properly complete manual labor such as farming and housekeeping. When they were not in class, they were expected to do the upkeep of the schools. Unclean and overpopulated living conditions led to spread of disease and many students did not receive enough food. Since diseases like tuberculosis were not yet treatable, children often died at these schools, without their parents’ knowledge or ability to give them a proper burial according to their culture. In the majority of schools, students experienced a variety of abuses—everything from sexual to physical to emotional and mental abuse. If students tried to escape, they often didn’t get very far—bounties were offered for them, and faced with unimaginable suffering, many young students resorted to taking their own lives. Sometimes students who died were buried in the school cemetery in coffins made by their classmates.

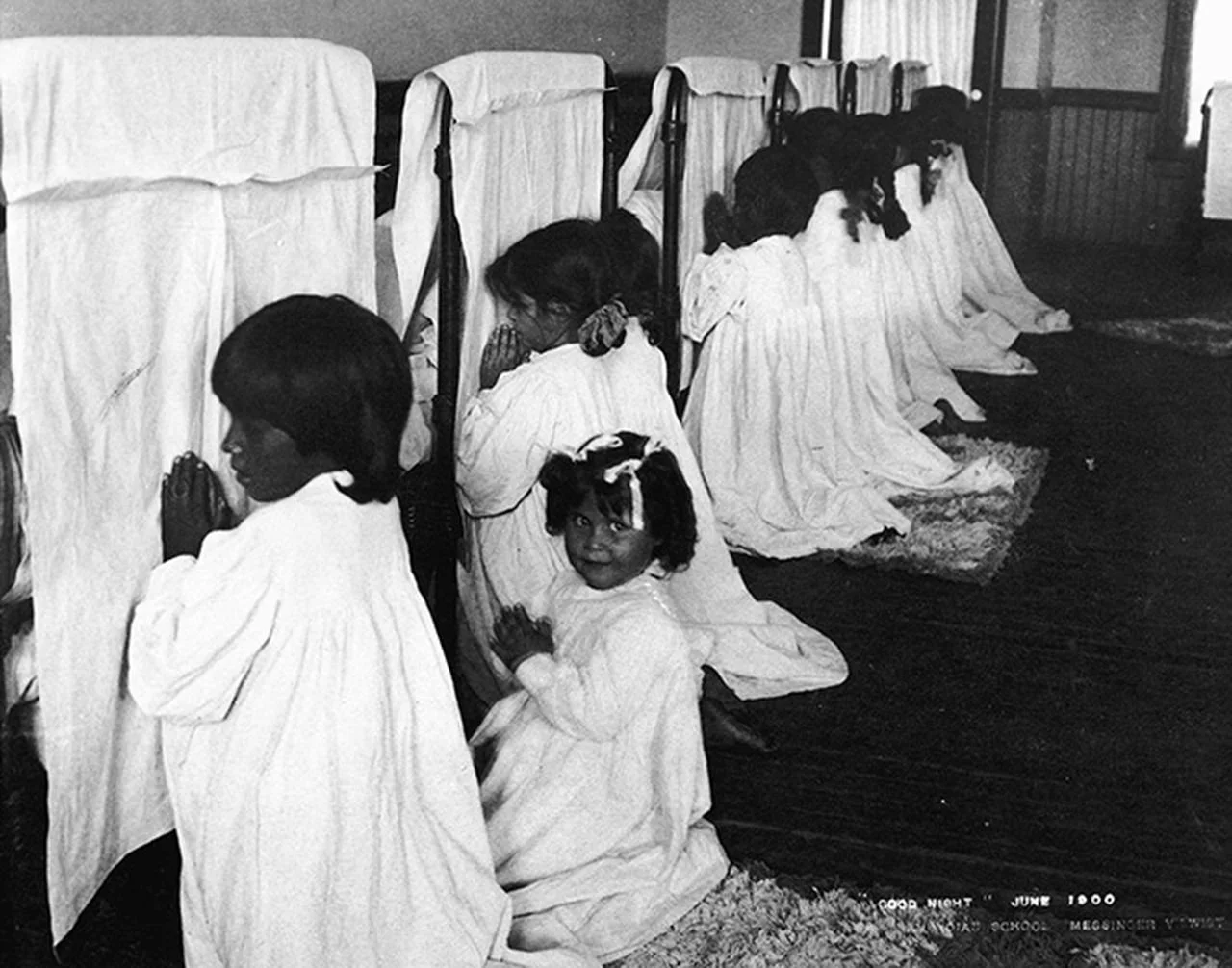

Students were forced to adopt Christianity and cut off their hair, which was a deep cultural wound

Of course, no loving parent would send their children off to one of these places if they knew what was happening, but many native families had no other choice. Congress had authorized the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to withhold rations, clothing, and annuities of those families that refused to send students. Without another way to survive financially, many complied in giving their children up with desperation in their souls. They believed that at least their child would be fed and educated, but had no clue the kind of sadness and torture they would go on to experience. Sometimes resistant Native fathers found themselves locked up for refusal. In 1895, nineteen men of the Hopi Nation were imprisoned in Alcatraz because they refused to send their children to boarding school. These were choices no family should have ever had to make.

An undated image of hundreds of Native students at one such boarding school

So, so many native families today still know of someone in their own family or their community that was enrolled at a boarding school. Many people living today were encouraged to “forget” their culture, their traditions and their heritage. While these abuses continued, many settlers were unaware, or chose not to see the truth of what was happening in these institutions.

While these schools continued to be in existence well into the 1900’s (some still are continuing to operate, albeit in an extremely different fashion today) certain changes began happening in the 1920’s and 30’s, and eventually Native Americans were granted the right and ability to govern themselves and provide their own education to their own children. Slowly but surely, people began to see what was really going on behind closed doors at these “schools.” In a complex political environment, these changes happened slowly and were often complicated. Tides continued to turn in the early 1980’s as the Indian Child Welfare Act was passed in 1978 to allow parents to legally refuse their child being sent to a boarding school. Many schools died out in the 1980’s and 90’s as a result of this act. As the Bureau of Indian Affairs was given more power within itself, most of these remaining schools were transformed, slowly, into places where native heritage was honored and celebrated rather than treated as something to eradicate. Students are now allowed to read and write in their own languages, taught about their culture in a way that honors them, and prepared for college acceptance like any other high school. Today, there are almost 200 Indian schools in existence around the US, and they are but a shadow of what they once were.

Staff and students at Santa Fe Indian School in Santa Fe, NM

As native communities look to the future, remembering what happened in our past is crucial to retaining our heritage, and preserving our culture. These schools were state-funded and their purpose was not a secret: to erase what native life was as a whole. The gravity of what happened to thousands of students couldn’t possibly be communicated in one blog post alone, but I really wanted to start the discussion. If you want to learn more, a great place to start is The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. So, how do we prevent something like this from happening again? Let me know your thoughts in the comments!